The Art and Science of Loopology

There’s a point in every artist’s life when the work stops being something you do and becomes something you study. Not the academic kind of study—although that’s part of it—but the kind of study where you’re forced to examine why the sound coming out of your speakers feels alive. You begin to understand that creativity isn’t just expression. It’s architecture. It’s engineering. It’s the push and pull of frequencies wrestling in the air until they form something that didn’t exist ten seconds ago. That push and pull—those small collisions between science and instinct—is what Loopology is built on, and the heart of it all is something simple, almost primitive: a speaker, a microphone, and a room.

If you strip Loopology down to its bones, the whole method hinges on one idea—sound changes when you let it leave the digital world and touch air. That one idea changed the course of my music forever. I didn’t want clean loops. I didn’t want neutral room tone. I wanted something with a pulse. Something unpredictable. Something that breathes. And that meant learning to trust what most audio engineers are trained to avoid: nonlinear behavior. Distortion. Resonance. Coloration. The chaos introduced by a real room.

When you re-mic audio—playing sound through a speaker, letting it spill into the air, and capturing it again with a microphone—you’re not just recording. You’re collaborating with physics. You’re sculpting energy. You’re manipulating the way frequencies decay, the way they collide with walls, the way bass swells as your room becomes part of the instrument. Re-mic’ing isn’t a trick. It’s a conversation. And Loopology is that conversation turned into a language.

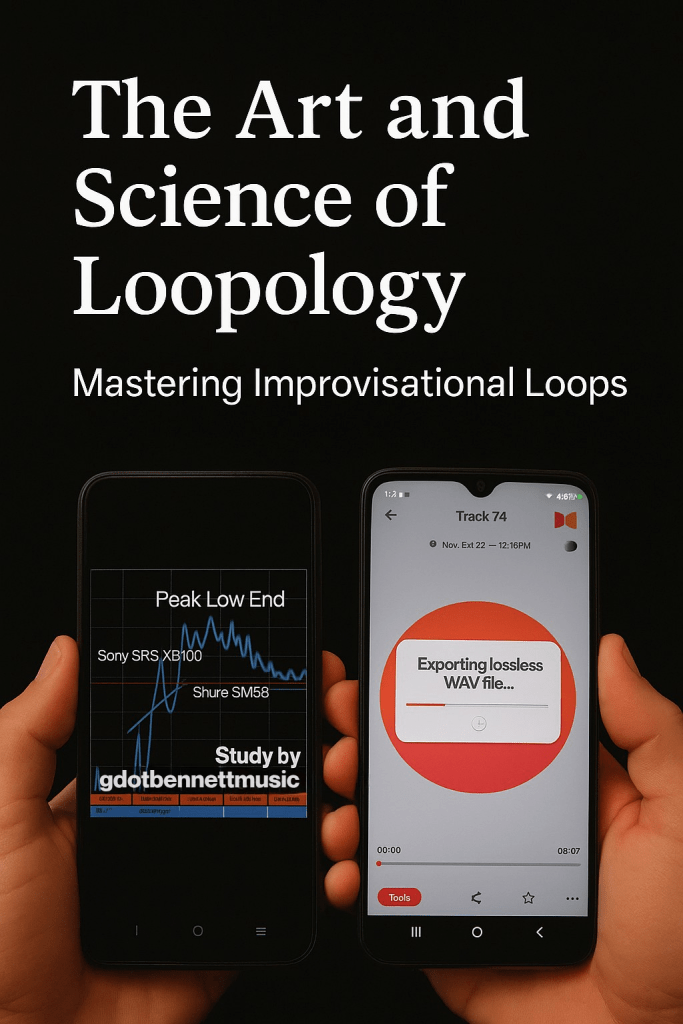

Anyone who’s ever stood in front of a subwoofer knows that bass isn’t just heard—it’s felt. The Sony SRS-XB100 speakers I use aren’t studio-grade monitors; they’re compact consumer speakers with one massive advantage: a low-end swell so exaggerated it’s almost reckless. On paper, any engineer would tell you that’s a flaw. But in practice, it’s the cornerstone of the Loopology sound. When that bass blooms, it gives me a foundation—something raw and heavy that pushes air with an attitude no plugin could ever replicate. When it hits the room, the room responds. There’s a shape to it. A personality. A willingness to misbehave. That misbehavior is the magic.

Then there’s the Shure SM58, a microphone designed to survive bar fights and still spit out a clean vocal. It has a presence boost right where human ears cling to clarity, and a natural roll-off in the low end that keeps the XB100’s bass from becoming mud. The SM58 isn’t just capturing the speaker—it’s sculpting it. It takes the violence of the low end, trims it where it’s too much, and lifts the mids where emotion lives. Between the speaker and the mic, you get a kind of agreement: the XB100 creates the storm, the SM58 frames it, and the room does whatever it wants in between.

That chain—speaker, air, mic, RC-505—creates a loop that feels less like a recording and more like a living organism. When I stack loops, the imperfections multiply. They evolve. A transient from the first layer becomes an echo in the third. A tiny bump in the bass becomes a wave by the sixth. I’m not building tracks—I’m growing them. Layer by layer, frequency by frequency, I’m watching the sound take shape like a sculpture that forms itself in slow motion. And the best part is that none of it behaves the same way twice. You can’t clone a Loopology session because you can’t clone a room, a moment, or the decisions your hands make when you’re improvising inside that moment.

This is where the science becomes art, and where the art becomes science. It’s the same mindset you feel when you watch a painter mix colors—not mechanically, but intuitively. They don’t measure the exact ratios; they watch how the brush drags. Loopology is the same. You learn to read the room’s response. You learn how far the SM58 needs to be from the XB100 to get the right kind of breakup. You learn the sweet spot where your low end starts breathing instead of bursting. And while anyone can technically replicate the gear, they can’t replicate the decisions. They can’t replicate your instincts. That’s the part no manual can teach.

When you push sound back into physical space, you start discovering things engineers rarely discuss: the emotional behavior of frequencies. There’s something about hearing a loop return to you with the little scars it picked up along the way—some added grit, a softened transient, a warm bloom on a note you didn’t expect—that makes you respond differently. You interact with sound reflexively, not analytically. You build intuition. You build flow. And that flow carries you through the performance as if the room itself is playing alongside you.

The more I worked with this method, the more I realized I wasn’t just looping—I was studying. Every frequency curve, every phase smear, every new shape added something to the language of Loopology. When I saw the frequency-response graph—the XB100’s massive low-end swell climbing like a wave, and the SM58’s steady contouring holding it in check—it felt like reading the blueprint of my own sound. Not because I designed the frequencies themselves, but because I designed the way they interact. That’s the difference between using gear and understanding it. And that’s why Loopology isn’t just a process—it’s a discipline.

You can’t perform Loopology without the willingness to let your tools surprise you. You can’t perform it without respect for the physics happening right in front of you. As a musician, you lean into emotion. As an engineer, you lean into observation. But as a loopologist, you hold both roles at the same time. The RC-505 becomes your canvas. The XB100s become your chisels. The SM58 becomes your translator. The room becomes your collaborator. And you learn to speak in echoes—the kind that soften, sharpen, or harden depending on how you respond.

The deeper I go into this method, the more I understand what makes it mine. It’s not the equipment—not really. It’s the relationship between the equipment, the environment, and the decisions you make under pressure. Loopology is guided improvisation, but it’s also structured experimentation. It’s emotion expressed through acoustic behavior. It’s science bending its rules just enough to let art take over. And when you hit that sweet moment—when the loop breathes back at you as if it’s alive—you understand exactly why this method matters.

Loopology reinvents sonic architecture because it doesn’t treat sound as a static object. It treats it as a material. Something flexible. Something responsive. Something you can shape not just with tools, but with intention. When you let the room become part of the performance, you’re no longer trapped in the digital world—you’re part of a dynamic, physical system. And when that system responds, it changes you. It forces you to react. It forces you to grow. It forces you to listen not just with your ears, but with your entire body.

The re-mic method isn’t about reinventing gear. It’s about reinventing the relationship between the artist and the sound. It’s about acknowledging that the loop doesn’t begin with the button you press; it begins with the air that carries it. And when you understand that, you stop looping just to fill space—you loop to communicate. You loop to transform. You loop to explore the moment you’re in. That’s what Loopology really is: discovery in real time.

And when the loop locks in—when the bass hits, when the mids lift, when the heartbeat of the track finally aligns with your own—it doesn’t feel like you built something. It feels like you met something. Something that was waiting to exist until you gave it permission. Something that wasn’t there until the speaker, the mic, the room, and your hands agreed to bring it into the world. That’s the beauty of it. That’s the science of it. And that’s why Loopology isn’t just a method.

It’s a living architecture.